Students: Quinton Denman, Maxine Hanrieder, Sebas Higler, Lianne Hufkens, Steffen Schneider;

Supervisor: Cameron Browne;

Semester: 2018-2019.

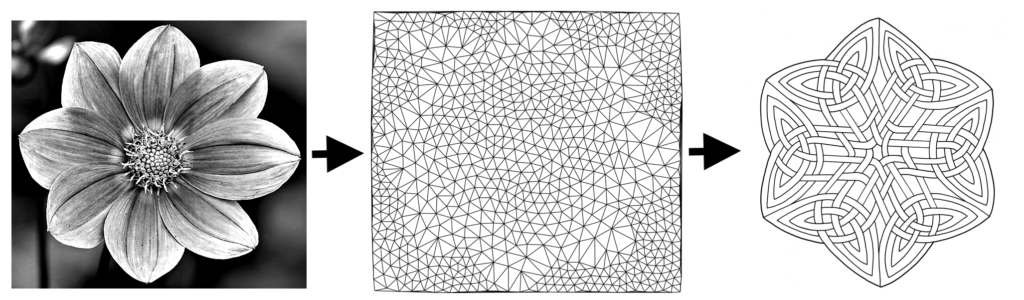

Fig 1. – General image that illustrates overall project. Left: Image of a flower. Center: Mesh rendering of the flower. Right: Celtic knotwork of the flower (this image shows an interpretation of the final result)

Problem statement and motivation:

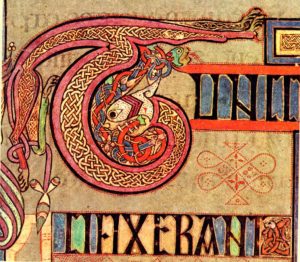

Celtic knotwork has a deep history dating back to 450AD originating with Celtic tribes (Bain, 1990). It has since developed into an artwork consisting of intricate and elaborate knotworks the style of which can be observed in the pictorial gospels called illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of the Kells (Brown, 1980) or the Lindisfarne Gospels (Backhouse, 1981). The knots consist of one or more looped strands woven together and follow a strict over-under pattern, visible in Figure 1. Celtic knotwork is, more often than not, an element within a larger artwork. It serves to add beauty but also imbues the artwork with the history and beliefs of the Celtic culture, see Figure 2. However, Kaplan (2003) mentions that “At some point after the 9th century the techniques used to create Celtic art were lost”, and further explains that George Bain (Bain, 1951) was responsible for reinventing the artistic techniques necessary to create Celtic designs. This technique was then simplified by Ian Bain (Bain, 1990), inadvertently creating methods resembling an algorithmic approach.

The research conducted will aim to understand and then stretch the limits of two aspects present within the challenge of automatically generating Celtic knotwork: the generation of a mesh from a grayscale or color image, capturing figures, shapes and internal features; applying authentic Celtic knotwork designs to said mesh whilst retaining the input images’ form and features. A challenge for the computer-generated knotwork will be to respect the rules implicitly used by traditional artists, ensuring that designs incorporate imperfections present in human work.

The research is not isolated and could lead to further developments in other fields. For example, the generation of a mesh that captures the internal features of an input image could have other applications in areas such as Robotics and Pattern Recognition. This serves to highlight the broader possibilities evident within the proposed research, stressing that whilst the application is very specific, the methods used to realize procedurally generated Celtic knotwork can be extended into other areas. Furthermore, the introduction of more Celtic knotwork could spread the history and culture to a wider audience.

Fig 2. – Authentic Celtic knotwork from Book of Kells.

Research questions/hypotheses:

The key research challenge in this project will be to generate a mesh from a given image that best captures the figure’s shape and internal features while remaining as regular as possible. Generating the knotwork from this mesh is expected to be comparatively straightforward. The research questions are formulated as follows:

- How can a mesh be generated to best capture the figure shapes and internal features of an image, while maximising regularity in the mesh elements?

- How can human-like Celtic knotwork best be generated from said mesh?

Main outcomes:

- The primary outcome of this project is a program that takes an image as input and outputs an image that depicts the input image’s features and shapes in Celtic knotwork style.

- From the input image a mesh generation method forms the basis onto which the knotwork is applied. The generated mesh ideally has a regular arrangment of predominantly quadrilateral elements. Moreover, the mesh’s density is inversly proportional to the intensity of the image (i.e. the mesh is denser in darker areas) to reflect the image’s depth in the knotwork.

- The knotwork adheres to a strict over-under pattern, the threads have some undulation and other attributes to mimic a human’s touch and it contains repeated motifs as found in authentic Celtic knotwork.

References:

Backhouse, J. (1981). The Lindisfarne Gospels . Phaidon Oxford.

Bain, G. (1951). The Methods of Construction of Celtic Art . W. MacLellan.

Bain, I. (1990). Celtic Knotwork . Celtic Interest Series. Constable.

Brown, P. (1980). The Book of Kells . Knopf; 1st American ed edition.

Edelsbrunner, H. (2001). Geometry and topology for mesh generation , volume 7. Cambridge University Press.

Fung, K. (2007). Celtic knot generator. BSc (Hons) thesis, University of Bath.

Gross, J. L. and Tucker, T. W. (2011). A celtic framework for knots and links. Discrete & Computational Geometry, 46(1):86-99. Kaplan, M. and Cohen, E. (2003). Computer generated celtic design. Rendering Techniques, 3:9-19.

Martin, D., Arroyo, G., Rodriguez, A., and Isenberg, T. (2017). A survey of digital stippling. Computers & Graphics, 67:24-44.

Mercat, C. (1997). Les entrelacs des enluminures celtes. Pour la science.

Reimann, D. A. (2012). Modular knots from simply decorated uniform tessella- tions. In Proceedings of ISAMA 2012: Eleventh Interdisciplinary Conference of the International Society of the Arts, Mathematics, and Architecture .

Secord, A. (2002). Weighted voronoi stippling. In Proceedings of the 2nd in- ternational symposium on Non-photorealistic animation and rendering , pages 37-43 ACM.

Son, M., Lee, Y., Kang, H., and Lee, S. (2011). Structure grid for directional stippling. Graphical Models, 73(3):74-87.